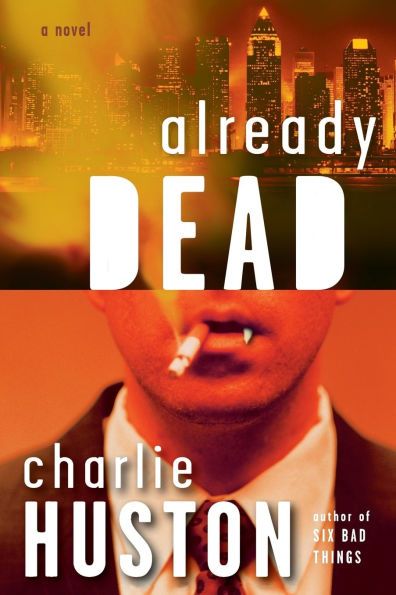

The Joe Pitt Casebooks came into my life a little earlier than they were supposed to. Already Dead hadn’t yet hit shelves, but a copy landed on my desk during a time when books arrived by the boxful, a relentless cascade of galleys and debut pitches. What nudged this one to the top of the pile was less its premise than the people whispering about it, Charlie Huston already had fans at the site I co-owned, and one of them, Brian Lindenmuth, a kind of noir evangelist, helped me with an interview with the author. Huston had currency in those circles. I just happened to be within earshot.

I’m not what you’d call a crime fiction guy. I like some of it, sure. But my tastes veer eccentric: I gravitate toward the speculative stuff, the Paul Auster neighborhood, where reality hums a little off-key, or Jonathan Lethem, who can fold noir into a surreal origami of Brooklyn sadness. I’ve got love for Finch by VanderMeer, dystopian fungal crime, go figure, and on the other side, thanks to my mother, I grew up with the armchair elegance of Poirot, the beefy smugness of Nero Wolfe. It’s more of a vibe than a genre for me. I hear podcasters I love like Chris Ryan and Andy Greenwald wax poetic about legendary crime novels and I nod along, making mental notes I rarely follow up on. My literary home is elsewhere, somewhere closer to Kazuo Ishiguro’s quiet devastations or the baroque riddles of Mark Danielewski.

And vampire fiction? Less said, the better. It’s never held much fascination for me. I’m not a Universal Monsters romantic. If you asked me to list vampire books I’ve loved, I’d run out of fingers after one hand, and a couple of those would be Dan Simmons novels, an man with great books but highly questionable takes.

So how did a vampire crime series set in New York City, written in a clipped, rat-a-tat voice, end up one of the few genre series I return to, and recommend without hesitation?

I’m not sure. Maybe it’s the how of Huston’s writing, his gift for rhythm, his dialogue that feels like a subway punch-up or a dive bar monologue. Maybe it’s Joe Pitt himself: brooding, broken, a little funny, often monstrous. Huston somehow makes the tropes feel hand-carved rather than store-bought. It helps that these aren’t just crime stories with fangs tacked on, or vampire tales dipped in noir. They’re deeply New York stories, sweaty, blood-slick, subway-rattled. They reek of stale beer and old piss and secondhand hope.

The books don’t glamorize much. They’re more bruised than bloody. And Huston keeps the mythology lean: clans instead of covens, turf wars instead of romantic triangles. If Anne Rice gave vampires aristocracy, Huston gives them rent payments and parole officers. This isn’t supernatural fantasy, it’s ecosystem. Gritty, territorial, strange.

I still don’t know why this never became an HBO series. The pitch writes itself. Though, to be fair, I’d probably hate seeing a story so locally haunted—so entrenched in the smells and scabs of New York get filmed in Bulgaria or on some suspiciously clean set in Atlanta. Joe Pitt doesn’t belong in tax-break fiction. He belongs to a city that’s always slightly decaying, always breathing steam through sewer grates.

Let’s start with a lie: that this is a vampire story. That’s how Charlie Huston gets you. That’s how Joe Pitt gets you.

Because the books are shelved under horror. Or noir. Or crime. Or fantasy. But really, this is plague literature. Addiction lit. A five-part junkie prayer written in blood and spit and bad decisions, set in a New York where the monsters don’t hide, they vote, they gentrify, they unionize.

The Joe Pitt Casebooks aren’t about fangs. They’re about systems. Infection as metaphor and infrastructure. Power mapped across boroughs like veins under translucent skin. You don’t read these books so much as get bit by them. Five novels: Already Dead, No Dominion, Half the Blood of Brooklyn, Every Last Drop, My Dead Body. A body count, sure. But mostly just a body, slow-rotting.

And at the center? Joe. Not a good man. Just a man who still wants to believe he might’ve been one, in a different city, with a different virus, in a different century.

He is a vampyre. Don’t call him that, but also don’t not. The Vyrus (yes, Vyrus, capital V, like a brand name) lives in him now, symbiotic, unstoppable. He feeds, he heals, he ages slower than guilt. He works as a sort of private muscle-slash-scapegoat for the many, many undead factions carving up Manhattan’s underworld like a cold slice of bad pizza.

And Huston?

He writes it like someone chewing glass just to remember how pain works. Sentences clipped down to the tendon. No commas unless they draw blood. Dialogue that reads like people trying not to scream.

In Already Dead, Joe’s trying to find a missing girl, avoid his ex-girlfriend’s questions, and not get killed by his own employers.

That’s just the first 50 pages. He’s already broken. He’s already tired. He’s already used up whatever grace he had years ago, and he knows it. But the myth of noir is that if you just keep moving forward, you don’t have to deal with what’s behind you.

In No Dominion, the world’s already contracting. There’s a new drug making its way through vampyre veins, and Joe’s the blunt object they send to solve it. But every “case” is just an excuse to remind him he doesn’t belong anywhere. The vampire clans — the Coalition (corporate fascism), the Society (liberal lies), the Enclave (zealotry), the Hood (scar-tissue pragmatism) — they all want to use him. None of them want to save him. And he’s too proud to ask.

By Half the Blood of Brooklyn, everything’s poisoned. The blood, the politics, the history. Joe goes to Brooklyn to negotiate a truce and ends up triggering a massacre. Racism and colonization sit uneasily just beneath the skin of the story, until they don’t. Huston doesn’t let you look away. Joe doesn’t either. But he still pulls the trigger.

Then comes Every Last Drop, where the map of the world gets bigger, other cities, other powers, other horrors. And you start to realize: the Vyrus is global. The hunger is systemic. The infection isn’t just inside the body. It is the body. And Joe? He flinches.

Because some people are too wrapped around their own myth of self-reliance to realize they’re choking on it.

And so we reach My Dead Body, and it’s not a climax. It’s a decrescendo. The slow collapse of a man who’s burned every bridge, every favor, every inch of cartilage in his knuckles. The final book reads like a haunted man dragging his own corpse through a world that no longer needs him. His body’s failing. His enemies are winning. And the people who might’ve forgiven him are long gone.

But he keeps moving. Because that’s what Joe does. Not because he thinks he’ll make it. But because the alternative, stopping, feels too much like death.

Huston doesn’t give us neat arcs. These books are about erosion. They’re about the long, grinding tragedy of a man who keeps calling himself an outsider while kneeling at the altar of every institution he pretends to hate. Joe Pitt isn’t a rogue. He’s an enabler. He does the dirty work and then spits blood at the mirror. He calls it survival. We call it complicity.

And yet. And yet. There’s something unbearable in how hard he tries. Not to be good, maybe, he knows better, but to be better. To hurt less. To hurt others less. And when he fails, he doesn’t blame the Vyrus, or the city, or fate. He just tries again. Dumber. More desperate.

What’s left by the end isn’t redemption. It’s residue. A ghost of the man who might’ve been. A glimpse of the hero he was never allowed to become. A blood-soaked, quietly tragic reminder that sometimes survival isn’t a victory. It’s just what’s left.

Joe Pitt never asked to be your favorite anything. He’s not a role model. He’s a mirror, cracked, held up to the stories America tells about what makes a man worth saving.

And Huston, sharp, merciless, furious Huston, never lets you forget the price of being that mirror. Even when it kills you.