While I often think fans of comics—and by extension, their creators—can become too preoccupied with the same ailment that afflicts some fantasy and science fiction writers, trading the walking stick for the mirror and then standing so close they fog up the picture, Brian K. Vaughan defies that pattern. He exists in both worlds: one foot in fandom, the other in creation. And in The Escapists, a project born of another plane-walking scribe—Michael Chabon, whose The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay surely won Pulitzers across the multiverse—Vaughan demonstrates his mastery of both.

The Escapists is many things. It is, at its heart, a tight, focused story following Maxwell Roth, a young man who cannot accept a world in which his beloved pulp hero, the Escapist, is no longer published. So he chases the dream—literally—by buying the rights with the last of his inheritance. To many, this would seem pathetic. A hopeless fantasy. But for Roth, it’s necessity. And those who help him revive this dream are real people, met in real life, doing real things. There’s no lab, no digital dungeon spun from ethernet and caffeine. This isn’t Ellis digging through e-trash to strike narrative gold. These are connections forged the old way.

Case Weaver, his artist, is found on the job—he maintains elevators, she’s a fellow worker just trying to escape the corporate grind. Later, she reframes the project’s meaning for Roth in ways he didn’t expect. His letterer, Denny Jones, is the childhood friend who always protected him—an actual superhero in the kind of world that doesn’t believe in them anymore. In a few short issues, Vaughan chronicles their efforts—the rise of their Golden Key Studios—and even their brush with corporate interest in a “marketing stunt gone wrong,” saved not by calculation but by a happy accident.

For those unfamiliar with Vaughan’s talent—or those who need their comics to come spandex-wrapped and action-stuffed—this might sound yawningly dull. It’s not. I won’t belabor Vaughan’s command of pacing, dialogue, and delivery, nor his uncanny ability to make fictional biography feel like universal coming-of-age. I’ll just tell you: there are superheroes. There are villains. And the comic dances between the “real” world and the world of The Escapist—his original Golden Age form and his modern revival. “Shift” is too clumsy a word; these narratives layer, and when viewed together—or peeled apart—they offer something expansive. An enhanced landscape.

One of The Escapists’ many achievements is how it allows modern readers to stroll into past ages of comics without the baggage of preconceived dismissal. The Golden and Silver Ages often carry reputational kitsch, a sense of detachment from modern sensibilities. I say this as someone who collects those very eras and still feels the gap. But Vaughan, paired with top-tier artists, shows you the fire that once burned off those pages. These pulp pioneers weren’t escaping anything—they were living in possibility. As within the pages of The Escapists, there were no boundaries.

When the Escapist comic gains popularity, the corporate machine comes knocking. But Vaughan resists the urge to villainize them. He’s no creator’s crusader. The offer is fair, we’re told. The heartbreak comes not in the check but in what it means, reflected in Case’s reaction to Roth’s acceptance. The description of this work as a “love letter” is apt. Love letters are rarely about the recipient. They’re written for clarity—for ourselves. Though The Escapists looks backward, its message is posted to the future.

All fiction is escapist, yes. But The Escapists is not a call to retreat from hardship into fiction. That’s never been Vaughan’s mode. Across all his work—Y: The Last Man, Saga, Ex Machina, take your pick—he avoids escapism as a crutch. If anything, he mistrusts it. He’d rather limp toward reality than sprint away. The titular message is not about escape as evasion—it’s about getting lost in the pursuit. The thrill is not in inhabiting someone else’s dream, but in chasing something of your own.

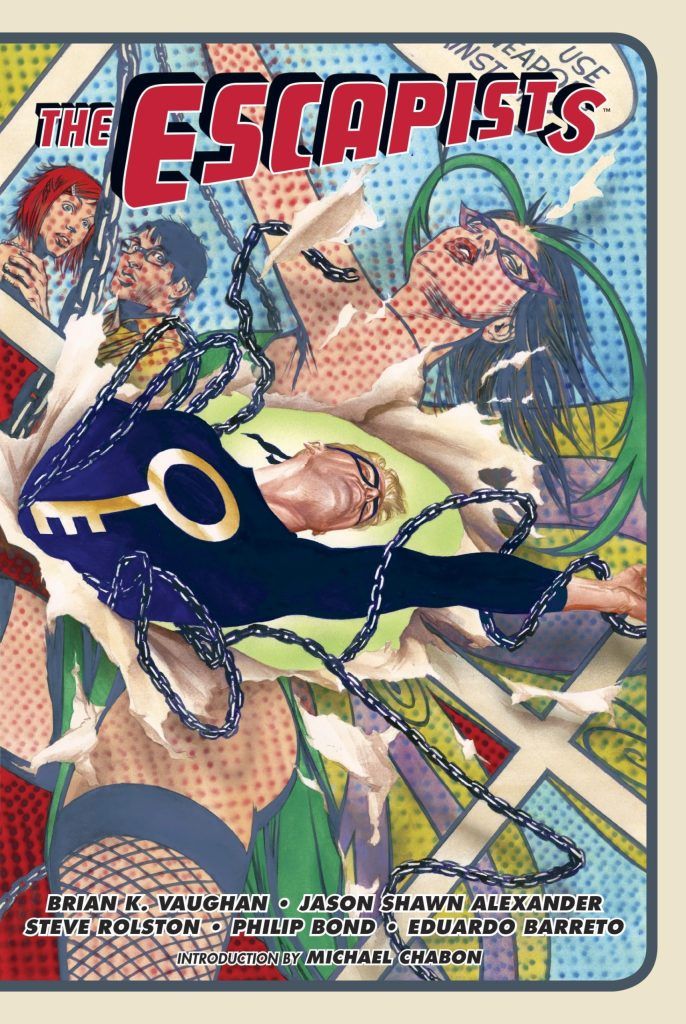

The true achievement of the art in The Escapists—by Jason Shawn Alexander, Eduardo Barretto, Philip Bond, and Steve Rolston—is capturing the inward journey and the meta-fictional one. The real quest isn’t Atreyu’s—it’s Bastian’s, reading the book. This is a fictional story about fictional storytellers creating fiction, and sometimes, finding themselves in the story—not by breaking the fourth wall, but by creating the sixth.

Literary readers will recognize this device—the story within the story, the book as portal—from House of Leaves, Shriek: An Afterword, Borges, Lovecraft, and others. But Vaughan and the art team give this device a seamless physicality. The vintage pages are nostalgia made kinetic. They stir a hunger to explore those eras where books bore titles like Weird, Amazing, Planet Comics, Two-Fisted Tales. The modern pages echo Totleben and the post-Moore revolution. Each visual style is a bridge—between generations, genres, realities.

I didn’t go to comic conventions as a kid. They were mythical. I was overseas, or too far away, or too broke. My convention was a flea market. That was my magic kingdom. Every weekend, I met Hama, Gaiman, McFarlane, Claremont, Shooter, Lapham—not in person, but in pages. I remember the awe in hushed debates: “Who is this Stephen Platt?” “I don’t know, but I’m coppin’ Moon Knight.” I was there when Generation X wasn’t just another X-book, but the one carrying the mutant torch. When Hellboy arrived in Next Men. When Gaiman and Moore rewrote the boundaries of the craft. When Image sparked something real. When Kraven’s Last Hunt dropped jaws.

Vaughan goes beyond knowing how to tell a story. He knows what stories are, and why they work—and then dares to tell you not to do what he just did. He’ll close a window you didn’t see. One that wasn’t even there.

Any child who has ever dreamed—and any adult not living that dream—should lock themselves up with The Escapists and watch it break free. Then, maybe, you’ll understand: Vaughan isn’t following Kavalier or Clay. He’s chasing what they chased. That invisible yet. The unreachable.

Some may criticize The Escapists for being less exciting outside the superhero interludes. I get it. The shifts in art and tone draw you in. It’s beautiful. It promises the amazing. It’s what comics are meant to do—simulate that moment when you transition from the mundane to the marvelous. That’s the escape.

I usually quote favorite lines in my reviews—sometimes profound, sometimes just smirk-worthy. With The Escapists, I nearly skipped the habit. Every line sings in harmony. But Vaughan opens his portion, right after Chabon’s table-setting, with this:

“Superman and I have the same hometown.”

We all do. As comic fans, our heroes trace their lineage to him. And yet we’re all aliens, too. Vaughan evokes an atmosphere that spans decades—a shared language between wildly different people. Comics gave us that. This thing of ours. We all came from different worlds, landing in the same place. A dreamscape printed on newsprint.

With Vaughan, you don’t just escape.

You arrive.